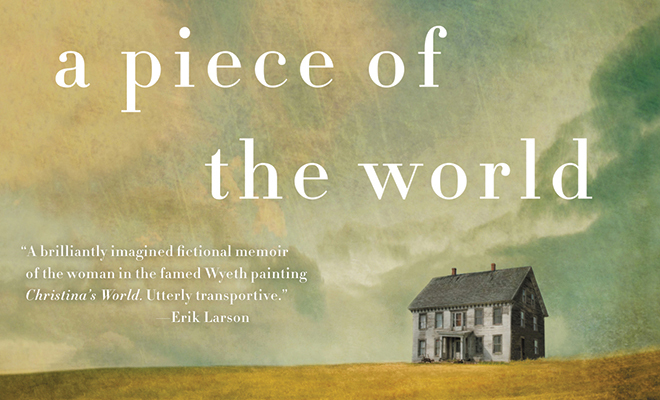

A Piece of the World by Christina Baker Kline

Christina Baker Kline is the author of six novels, and her work has appeared in the New York Times, Money, Psychology Today and many others. She lives near New York City and on the coast of Maine.

The image in the painting evokes a sense of mystery. “Christina’s World,” by Andrew Wyeth, shows a young woman in a pink dress crawling toward a desolate house atop a stark hill covered with rough grass. We sense that she cannot walk, that she is crawling to the house with no one to help her. Christina Baker Kline, author of the best-selling Orphan Train, gives that young woman a name, a voice and a story to tell.

She is Christina Olson, born in 1893 on a remote 100-acre farm in Maine. The large farmhouse was built by Christina’s ancestors, who left Salem, Massachusetts, in the mid-1700s after the infamous witch trials. Although the painting doesn’t show it, the farmhouse overlooks the coast. The sea played an important role in Christina’s family history, her father was a Swedish sailor stranded by a storm who met her mother when he knocked on the farmhouse door for help.

Christina is the narrator of her story, which she tells in disjointed pieces. She and her three brothers are expected to work full time on the farm once they become teenagers. Despite being affected by an unknown progressive disease that weakens her arms and legs, she helps her mother with cooking, cleaning, sewing, butchering, preserving and all the other domestic tasks associated with farm living. Her life is defined by chores that mark the passing of the seasons.

She likes school and attends until she’s 12, limping along the road to the one-room schoolhouse each day. Her teacher suggests that she continue her education and take over her job when she retires, but Christina’s father said she can’t be spared and her mother agrees. Christina’s world begins to shrink.

In her early 20s, Christina sees a ray of hope in the person of Walton Hall, a summer visitor to the nearby town, who courts her for several years. He’s a Harvard student and offers the promise of escape from the farm and its drudgery. Because Christina tells her story the way memory works, not always in chronological order, we know before she takes us to the end of the relationship that it will not be the escape she hoped for. Her world shrinks again.

The Olson parents are proud and set in their ways. Through the 1940s, they live without electricity or indoor plumbing. When Christina throws a tantrum about seeing a doctor as a child, they decide to never take her again. She seems to have inherited their stubbornness when later, as an adult, she refuses to use a wheelchair when she can no longer walk.

Kline is unsparing in her description of the harshness of life on the farm, of the unending cycle of tedious tasks to be completed. As she showed in Orphan Train, she is a faithful chronicler of the hardship of life for rural women. She also provides lyrical descriptions of days lived closed to nature, where the beauty of spring and summer is made more precious by the harshness of winter. Kline seems to drawn inspiration from Wyeth’s work for her writing style, which is spare yet instilled with strength and depth, similar to his paintings.

Time passes and finally it’s just Christina and her brother, Al, in the old farmhouse, easing into old age and trying to hold time at bay as the farm and its buildings fall into neglect around them. Walking becomes more difficult and finally impossible for Christina. Then their days are brightened by the appearance of Andrew Wyeth, an aspiring painter and son of the famous illustrator N.C. Wyeth. His wife, Betsy, is an old family friend who was drawn to the farm as a child. Before long, her husband feels the same pull.

Wyeth draws inspiration from the dilapidated farm and the faded grandeur of the imposing farmhouse. By the time he sees the house in the late 1930s, its paint is peeling and tattered lace curtains flap at the windows. Many of the upstairs rooms are unused, so he converts one into an art studio that he visits almost daily during the summer. He is a welcome visitor who makes life much more interesting for Christina.

Wyeth painted many scenes from the Olson farm, including realistic portraits of both Christina and Al. For “Christina’s World,” he showed its middle-aged subject as she saw herself, as a young girl. For all those who have ever studied the image in “Christina’s World” and wondered about the woman on the hill, A Piece of the World provides a hopeful suggestion of how she may have lived. ■